kó presents Nike Davies-Okundaye at Frieze Masters London in the Spotlight section, dedicated to pioneering women artists of the twentieth century.

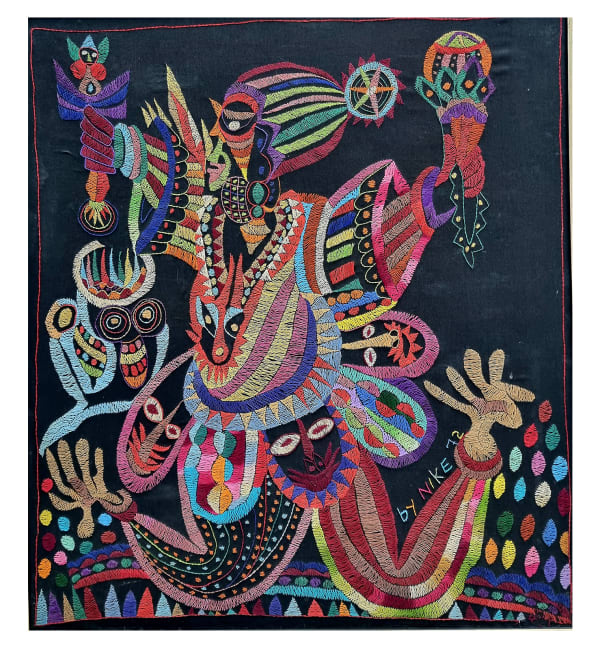

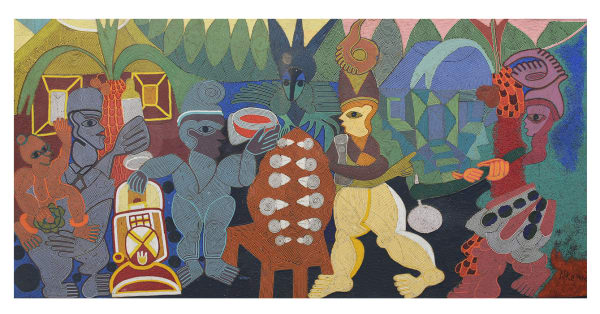

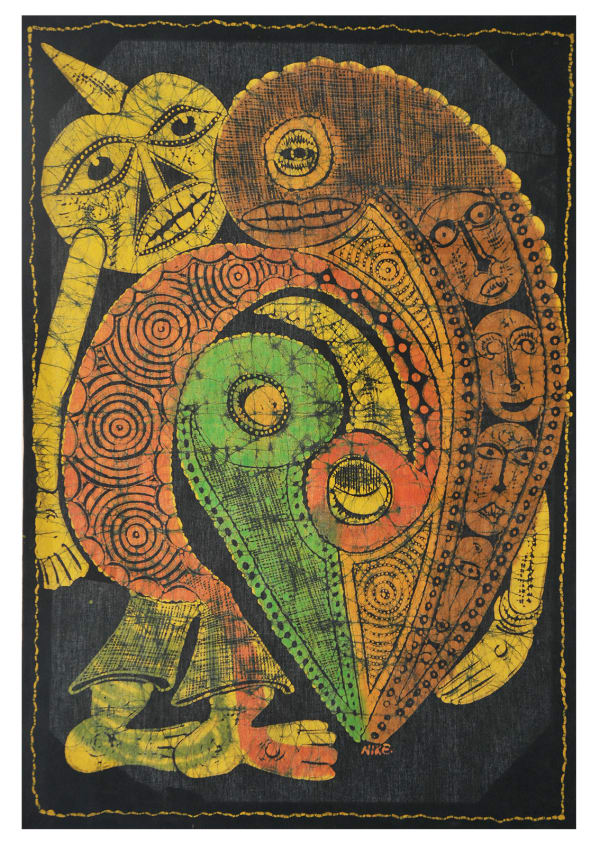

This presentation highlights the artist’s groundbreaking work in textiles, dyeing, weaving, beadwork, painting and embroidery, from the 1960s-1980s.

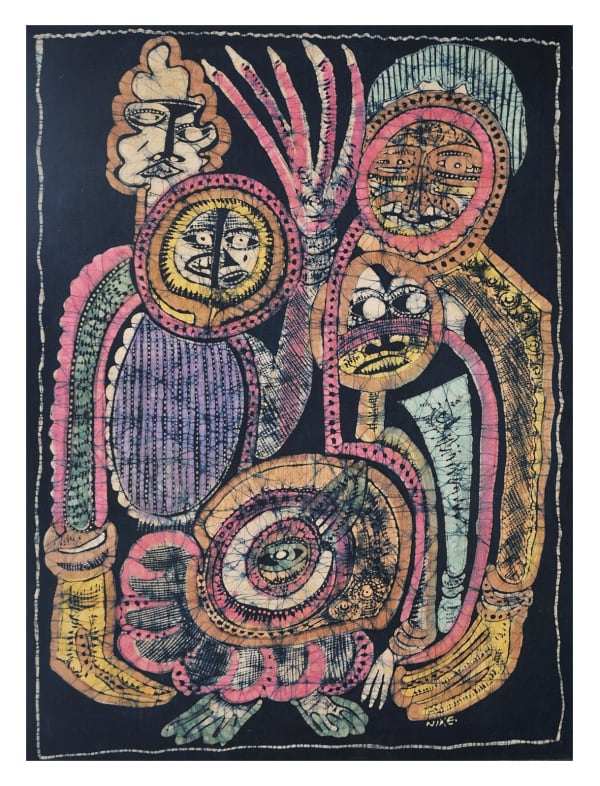

Chief Nike Davies-Okundaye is an internationally renowned batik and Adire textile artist. Born in 1951 in Ogidi, Nigeria, she is a central figure in the revival of traditional Nigerian arts with a career that has spanned more than five decades. She is best known for her exploration of Adire designs, a traditional Yoruba technique using indigo dyes on hand painted cloth. Traditional Adire designs embody cultural and historical meanings, combined into larger overall patterns that are recognized in Yoruba culture. She was particular drawn to its cultural significance as a “woman’s art,” passed down by successive generations of women. Nike was inspired by old methods of weaving and dying that were fading away.

With no formal art education, Nike is a fifth-generation artist from a family of craftsmen. She became an apprentice to Susanne Wenger, an Austrian artist living in Osogbo, a major center for art and culture in Nigeria. She became known as part of the Osogbo Art Movement of the 1960s, which arose in the newly independent Nigeria. With an interest in Yoruba spirituality, the Osogbo School focused on re-engaging traditional artistic practices alongside elements of modernism. Affectionally known as “Mama Nike”, she is a seminal figure of the Nigerian art community, with four art centres throughout the country.

Nike began weaving at the age of six, learning from her great-grandmother who was a weaver and Adire textile maker. Her first solo exhibition was held in 1968 at the Goethe Institute, Lagos. Since then, she has held over 102 solo art exhibitions and participated in 36 group art exhibitions. In 1974, Nike was one of ten African artists who toured and taught arts in various crafts institutions in the United States, taking her to all fifty states to conduct workshops and deliver lectures in schools and community centers. She has continued to serve as a guest lecturer in traditional textile techniques at universities worldwide, including Harvard University. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Museum, National Museum of African Art, in Washington DC; the Gallery of African Art, London; The British Library; the Victoria and Albert Museum; the Museum of Natural History, New York; Iwalewa-Haus, University of Bayreuth, Germany; and Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth, among others.

Alongside her artistic practice, Nike is known for her support of women in the craft industry. She is the founder and director of four art centers in Nigeria that offer free training in visual, musical and performing arts. In Osogbo, she teaches indigo cloth-dyeing techniques to rural women. She is the owner of Nike Art Gallery, the largest private art gallery in Africa with over 8,000 artworks spanning five floors.

In 2000, she was invited by the Italian government to train young Nigerian sex workers in Italy crafts, which led to aiding over 5,000 women by teaching them Adire production, weaving and other arts. She received recognition for her work by the United Nations and was awarded one of the highest Italian national awards of merit by the government of the Republic of Italy in appreciation of her efforts in using art to address and solve the problems of sex workers. She has received numerous awards for her contributions to Nigerian arts and culture. In 2004, she was appointed a member of the UNESCO Committee of the Nigerian Intangible Cultural Heritage Project. In 2005, the National Commission for Museum and Monument of Nigeria awarded Nike a certificate of excellence in recognition of her efforts in the development of Nigerian cultural heritage.In 2006, Nike was appointed a board member of the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria Tourism Board in Abuja, Nigeria. Nike holds the chieftaincy titles of the Yeye Oba of Ogidi-Ijumu and the Yeye Tasase of Oshogbo.

This presentation is organized by Kavita Chellaram and Joseph Gergel of kó, with curatorial support from Jareh Das.

About Jareh Das

Based between West Africa and the UK, Dr. Jareh Das is a researcher, writer and curator, whose focus of study has included the politics of clay, contemporary performance art with a focus on site-responsive performance in West Africa, and the work of Donald Rodney. Her interests in (global) modern and contemporary art are cross-disciplinary, although her understanding is filtered through the lens of performance art which informs both her academic and curatorial work. In 2022, Das was awarded a two-year early career fellowship from Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art as part of their New Narratives Awards. She holds a doctorate in Curating Art and Science: New Methods and Sites of Production and Display in partnership with Arts Catalyst and Royal Holloway, the University of London funded by Arts Humanities Research Council (AHRC); an MA in Curating Contemporary Art (Inspire), the Royal College of Art, London funded by Arts Council England (ACE); and a BA (Hons) in Material Culture, Architecture and Museum Studies from the University of Leeds.